The Ingredients

(Thinking through Materials)

On Lin Wang’s exhibition Exotic Dreams and Poetic Misunderstandings - The Silk Roads

Kunsthall Grenland

05.04 – 26.05 2019

Text/curator: Randi Grov Berger

An early example of Dutch Golden Age painting by Willem Kalf (1619-1693), entitled Still Life with a Chinese bowl, a Nautilus Cup and Fruit (1662).

At Blaafarveværket (the Cobalt Works), cobalt ore was first mined from open mines, and today these can be seen from the museum’s viewing points.

A Kobold illustration found online Encyclopaedia Britannica, amongst many unaccredited drawings.

Water jug decorated with the royal arms of Portugal (up-side-down). Image from The MET Museum.

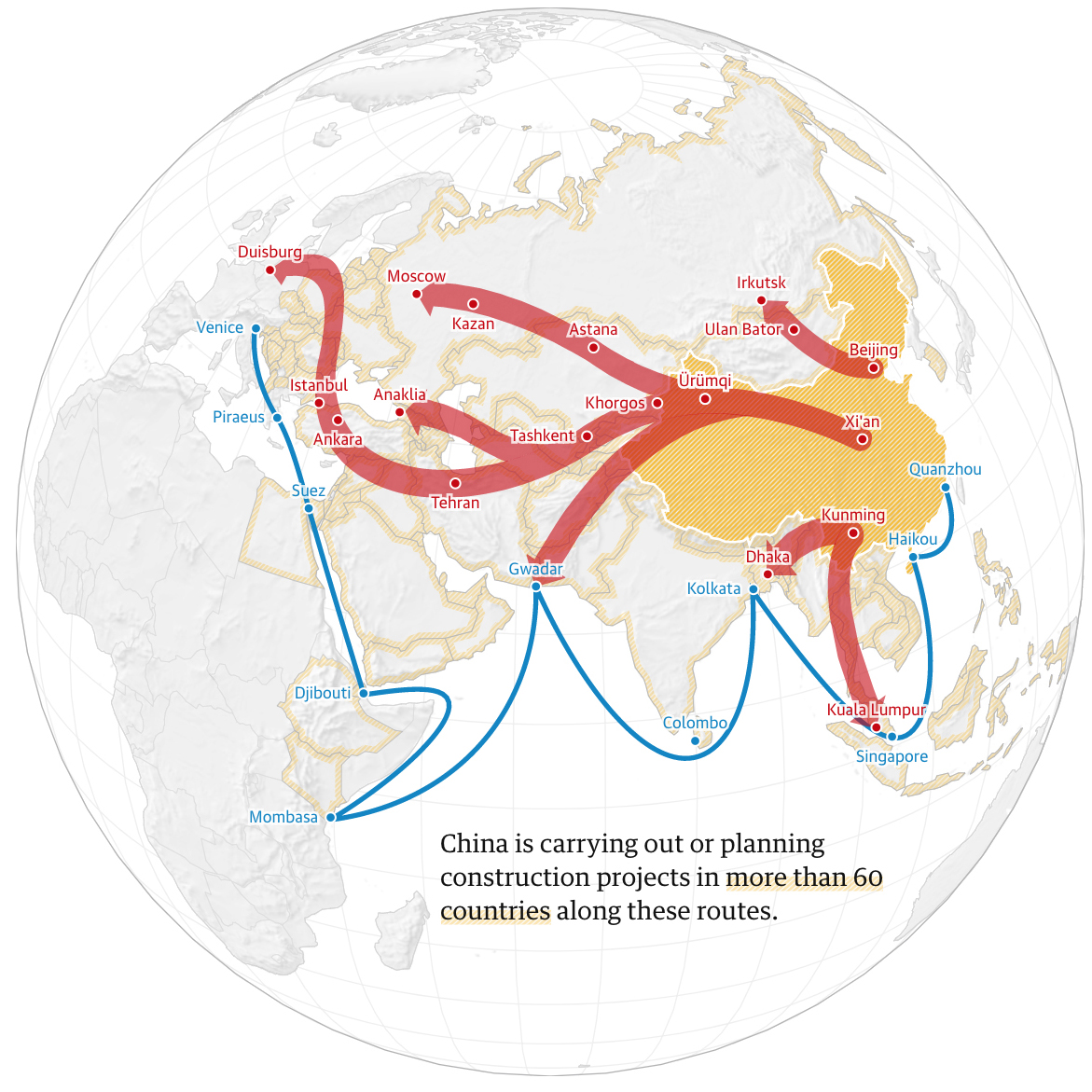

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is often described as a 21st century silk road, made up of a “belt” of overland corridors and a maritime “road” of shipping lanes.

Different shades of cobalt blue colour the more than twenty thousand handmade porcelain pieces contained within Norway-based, Chinese-born artist Lin Wang’s laborious installation at Kunsthall Grenland. Also in the exhibition space are smaller object-based works through which the artist represents human anatomy – spinal cord, bones, flesh, and tangent planes of the brain – richly decorated with symbols relating to her cultural background, to traditions within the field of porcelain, and to contemporary Western influences (Wang’s obsession with sailors’ tattoos is evident here). Combining and reinterpreting these varied references, Wang makes way for the “poetic misunderstandings” of her exhibition’s title while simultaneously highlighting similarities across expressions, linking them through trade and cultural exchange with specific emphasis on the “silk roads” of both ancient times and today.

“Exotic Dreams” refers to how Wang as a youngster was told myths about the North, and how she later moved to Norway and was confronted with a different reality entirely, while seeing her country of birth anew from a distance. Exoticism is a result of our perception of difference, or ‘otherness’. It is found in all corners of the world, generated through the continual process of constructing internal narratives while imagining, relating to and interpreting other cultures. Through her exhibitions and performances, Wang consistently reminds us that the cultures we create and the beliefs we project on others exist in a continual back and forth negotiation. Using the examples of China and Norway to underscore this dynamic, she expertly uses her craft to bridge cultures and create dynamic conversations.

When Wang moved to Norway in 2014 to begin the Master's Programme at the art academy in Bergen, the Ceramics department was in a state of flux; the integration of departments across the institution meant that Ceramics was no longer an independent field of study, although the technical workshops remained available. The international ceramics scene itself had been through a rapid period of change as contemporary craft became increasingly conceptual and contemporary art delved deeper and deeper into materials and craftsmanship. From her education in China, Wang brought a strong awareness of tradition within her field, and in Norway she adopted an enthusiasm to re-appropriate, transform and further develop the knowledge and character of contemporary porcelain. She found new ways to ‘steer her ship’ in these rough waters, and positioned herself in the middle of the current discourse around contemporary craft.

Wang’s work in porcelain has led to, and been used in, a series of ‘dinner performances’ that draw from the themes and aesthetics of 17th century Dutch still-life painting. These ‘sceneries’ have included extravagant dinner tables decorated with luxurious fabrics, flower arrangements, queen-size candlesticks, crystal glasses, and sharp cutlery. There is always an abundance of ‘exotic’ food and spices from all corners of the world, with their many distinct odours mixing and filling the air. Wang pours red wine from her heart-shaped porcelain fountains while locally scouted retired sailors sing shanties and recite poetry from their days traveling the seas onboard trading ships. The audience is invited to eat and drink, and gradually the unexpected symbols of Wang’s skilfully ornamented blue-and-white porcelain wares are discovered, along with their connections to the sailors’ tattoos of mermaids, pinup girls, tall ships and anchors. The exchange of cultures, food, religions, and ideas is inherent to trade routes; in Wang’s dinners they blend in surreal ways as guests share myths and stories while connecting the dots in a collaborative effort around the table. Through these works, Wang speaks to all our senses and touches the limbic system of our brain, giving us a direct experience of her themes and postulations.

Exotic Dreams and Poetic Misunderstandings - The Silk Roads is Wang’s largest exhibition to date. In preparing it, Wang worked from both her studio in Jingdezhen, China and her temporary work space in Porsgrunn, creating works that formally unite a variety of clays, glazes, and other materials, such as gold, that originate from regions along the historic Maritime Silk Road.

ELEMENTS

Kunsthall Grenland is located in Porsgrunn, in Norway’s Telemark region, which has a rich geological history that extends back over a billion years. The area is partly situated on what is called the Norwegian bedrock, consisting of granite and gneiss. Part of Porsgrunn’s city centre is positioned on a seabed initially formed south of the equator – a potentially dizzying fact. Here we find sandstone, slate, and limestone with rich organic content, which have laid the foundation for several industries in the area. Limestone, which once formed at the bottom of tropical seas (beautifully evidenced by ancient sea creature fossils), is now used in cement, plastics, paper, and toothpaste.

Further north of Porsgrunn is the village Åmot (in Modum, Buskerud), where cobalt formed the basis of a lucrative industry that was in operation from 1776 to 1848 (with reduced activity until 1898). Blaafarveværket (the Cobalt Works) exported up to 80% of the world's cobalt, which was sold to countries as far away as China. Cobalt was used for bleaching paper, and its blue pigments were prized for their intense colour. Once more precious than silver, cobalt was also used in glass and porcelain fabrication due to its vibrancy and its capacity to withstand the high temperatures essential to the production processes. The closure of the mines was partly due to competition from producers of synthetic ultramarine, which was invented in 1826 and replaced much of the need for cobalt.

Another location of relevance to Wang’s installation is the Chinese village of Gaoling in Jiangxi Province. Gaoling roughly translates as ‘tall hill’, and the area has a rich supply of white clay, from which Kaolin (from Gaoling) clay derives. Today the main use of the mineral kaolinite is to provide the gloss on several grades of coated paper. It is also used in cosmetics and toothpaste, and can be ingested as a medicine to soothe an upset stomach. It is generally known as a component of porcelain clay, and it is in Gaoling’s neighbouring village of Jingdezhen that porcelain production originated and still flourishes today.

It can indeed be absorbing to contemplate how the raw materials of the universe, which are traceable to stars in our galaxy, have dispersed and gradually formed our planet. How, most recently, their extraction fuels vast industries, affecting and transforming entire communities. How they circulate expeditiously through changing trade routes, catalysing the evolution of our habits and the growth and fluctuations of the world economy. Their usage shifts alongside human invention, technological advances, and changing climate. It is continually relevant to ask: where do we get them, what do we use them for, and how do they fit into our economy?

COBALT BLUE

Let’s take a closer look at one of the chemical elements central to Lin Wang’s work, which is also a basic building block of the universe. Cobalt, previously mined in Åmot, is not found as a free element, but in other minerals in the Earth's crust. The Periodic Table as we know it today, laid out in tidy rows and columns, was developed by scientists over three hundred years. Swedish chemist Georg Brandt is credited with discovering cobalt in 1735, and the new "semi-metal” was listed with symbol Co and atomic number 27.

Cobalt ore, a byproduct of copper and nickel, is difficult to extract and the smelting process is messy. This is partly why it was named after the kobold: spirits once thought to live underground. Superstitious miners believed the spirits lured them into taking worthless ore that caused a burning sensation to those who handled it. Medieval miners blamed the sprites for the poisonous and troublesome nature of the arsenical cobaltite and smaltite ores, which polluted other mined elements. Some insisted the kobold creatures were expert miners and metalworkers, and could be heard constantly drilling, hammering, and shovelling. Some stories claim the kobolds lived in the rock, just as human beings lived in the air.

The colour blue gained special significance in the history of Chinese ceramics during the Tang dynasty (618-907). In the 9th century, Chinese artisans abandoned the Han blue colour that had been used for centuries and began to use cobalt blue. Cobalt ore was first imported from Persia, where it was a scarce ingredient and used only in limited quantities. In the Yuan (1279-1368), Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties in particular, different types of cobalt ore and methods of application determined the distinctive shades of blue that appeared on blue-and-white porcelain ware. The plates and vases were shaped, dried, painted with a brush, covered with a clear glaze, and fired at a high temperature.

Lin Wang replicates these recipes. She uses Smalt blue from the Yuan dynasty, Xuanwu blue from the Ming dynasty, Kangqian blue from the Qing dynasty, and, in addition, incorporates a signature blend from Porsgrunds Porselænsfabrik (the Porsgrunn Porcelain Factory), for which the pigments are imported from Germany. These distinct forms of cobalt blue pigments, discovered, traded and utilized throughout numerous places and eras, now come together in Wang’s captivating, large-scale porcelain installation, creating vibrant connections across time.

WHITE GOLD

Porcelain owes its discovery to the people of Ancient China, who identified the exceptionally hard and solid matter that remained at the bottom of their outdoor fire pits as a useful building material. Mixing and firing local types of earth, they began creating simple jugs and bowls. Due to ongoing creative experimentation over the years that followed, porcelain became increasingly white in colour. Two thousand years ago, during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25 – 220), the porcelain produced would have been almost glass-like in appearance. The Tang Dynasty (618–907) that followed gave way to a rise in popularity of the ritual of drinking tea. Ceramics wares including teacups were touted all along the northern Silk Road, which originated in Xi’an and extended along the Hexi Corridor.

Porcelain remains a breathtaking medium to this day. The European name comes from the old Italian porcellana (cowrie shell) due to its resemblance to the shell’s surface. Porcelain is also referred to as china or fine china in certain English-speaking countries. Beginning in the 14th century, porcelain was exported in large quantities to Europe where it gave rise to a widespread form of imitation known as Chinoiserie. By the early 16th century, after Portugal established trade routes to the Far East and began commercial trade with Asia, Chinese potters began producing objects specifically for export to the West, and porcelains began to arrive in even greater amounts.

As the export trade increased, so did the demand from Europe for familiar, utilitarian forms, such as mugs, ewers, and candlesticks. These forms were unknown in China, so models were sent to Chinese potters to be copied. Their production and exportation facilitated a form of cultural transaction between the Far East and Europe based on the appropriation of physical models and selected Chinese patterns. This exchange embodied the European perception of China’s ‘exoticness’ and did little to foster cultural and social insight. An early example of export porcelain is a water jug decorated with the royal arms of Portugal; the arms, however, are painted upside down – a reflection of Chinese unfamiliarity with the symbols and customs of their new trading partner.

The Dutch engaged in lively trade with China, and in the 17th century they imported millions of pieces of Chinese porcelain. Using the Jingdezhen porcelain as a model, Dutch craftsmen created their own unique ceramics. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Delftware ceramics became known worldwide, and were promoted as typically Dutch products. The first Delft Blue ceramics, however, were ordinary copies of the traditional blue-and-white porcelain pieces crafted in Jingdezhen. Dutch-style ceramics were not made from typical porcelain clay, but from clay coated with a tin glaze after being fired, and achieved unrivalled popularity. At the industry’s peak, there were thirty-three ceramics factories in Delft. Of these, the only one remaining is Royal Delft, which is still in operation.

With the appearance of numerous porcelain factories in Europe, the demand for Chinese export porcelain began to diminish, and by the second half of the 18th century the trade was in serious decline. The porcelain industry found its way to Porsgrunn, where Porsgrunds Porselænsfabrik was established in 1885. The river Ælva and the existing shipping industry provided opportunities to bring in raw materials and transport finished products. The ingredients quartz and feldspar were found close by, and kaolin and coal could be delivered by ship. With these components, Porsgrunds Porselænsfabrik could produce their own blend. Porcelain had been a luxury commodity in Europe during the 18th century, but the social reforms and higher standards of living of the 19th century led to a sharp increase in its demand. The city of Porsgrunn was favourably located to ship to the large and growing markets in Norway and Sweden, and the factory soon became famous for its quality and designs, which included the blue-and-white straw-patterned tableware set. As the factory grew larger, the young men of Porsgrunn were faced with a choice between two contrasting professions offering equal potential for financial success: sailor at sea or factory worker at Porsgrunds Porselænsfabrik – a transitional moment that truly coloured the region’s identity and is built into the history of many generations of its citizens.

But making porcelain was never easy. It demands precision, and each step must be perfected. It can be difficult to imagine, when holding a porcelain object, the long journey the material has taken. The process comprises many stages: extracting the raw material, perfecting the blend of components such as kaolin and water, making the mould (which is produced about 20% larger than the finished design to account for shrinking), applying the finishing touches after the first firing in the kiln using customized glazes, colours and patterns. Then comes the terrifying “make it or brake it” final firing at up to 1400 °C, which yields either cracks or perfection. If finished perfectly, the porcelain’s properties include low permeability and elasticity; considerable strength, hardness, toughness, whiteness, translucency and resonance; and a high resistance to chemical attack and thermal shock.

“MADE IN CHINA”

Today, most of Norway’s porcelain production is outsourced. At the height of its operations, Porsgrunds Porselænsfabrik had more than five hundred employees, and the factory remained one of the district's largest and most important companies until the 1990’s. Some porcelain continues to be produced in Porsgrunn, and the factory’s characteristic straw pattern in cobalt blue is still painted by hand by local specialists. But production sites such as this, along with Blaafarveværket in Åmot, are increasingly transforming into museums and tourist attractions, signifying a shift to the service industry as the dominant business model of the area.

The fact that most things we own are produced elsewhere is worrisome in that, amongst other things, it causes us to lose touch with the materials that surround us, that constitute the objects of everyday life; teacups, clothes, and even smartphones. We no longer know where these materials came from, who made them, and the time it took to get them to us. Let’s return again to cobalt: as a metal, it has unique magnetic properties, making it essential in modern technology. It is used in our mobile phone batteries, for example. Around 80% of cobalt today is extracted in Congo, Africa, where China increasingly has a stranglehold over the supply due to their large investments in the infrastructure of the region, which constitutes part of their Belt and Road Initiative, also known as the New Silk Roads. More than ever, cobalt is a metal associated with conflict, child labour and unethical production, like so many other raw materials we import and are dependent upon.

Currently there is a team of researchers working to map critical minerals in Europe, to see where they appear and gauge the potential to extract them closer to home. We can therefore not exclude the possibility of cobalt and other mineral mining industries returning to Norway in the not-so-distant future, as technological shifts and climate change continue to influence the demand, as well as the world economy and our ethics and behaviour.

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS

Porcelain ware is firmly positioned within the long genealogy of global trade; it brings together the past and the present both through its ingredients and references. The materials, the glazes, the tools and the processes remain constant, but perspectives on porcelain have consistently changed. Lin Wang, like many craft-based artists, offers an alternative to the mass-produced object. By rethinking established ideas surrounding ‘seeing’ and ‘knowing’ – influenced by our condition of colonialism and globalization – her work argues for porcelain’s renewed relevance.

The Maritime Silk Road offered a sea voyage from the known to the unknown; it is where civilization itself began, where the world's major religions were born and took root, and where languages, ideas, and diseases spread. It is where empires were lost and won. It was – and its new versions remain – the world's central nervous system. The enduring rise of China as a superpower and its ambitious New Silk Roads provide at this very moment unprecedented conditions for global trade. Just as human anatomy elucidates how the body functions, understanding these networks and infrastructures will allow for a better grasp of the world we inhabit.

© Randi Grov Berger 2019